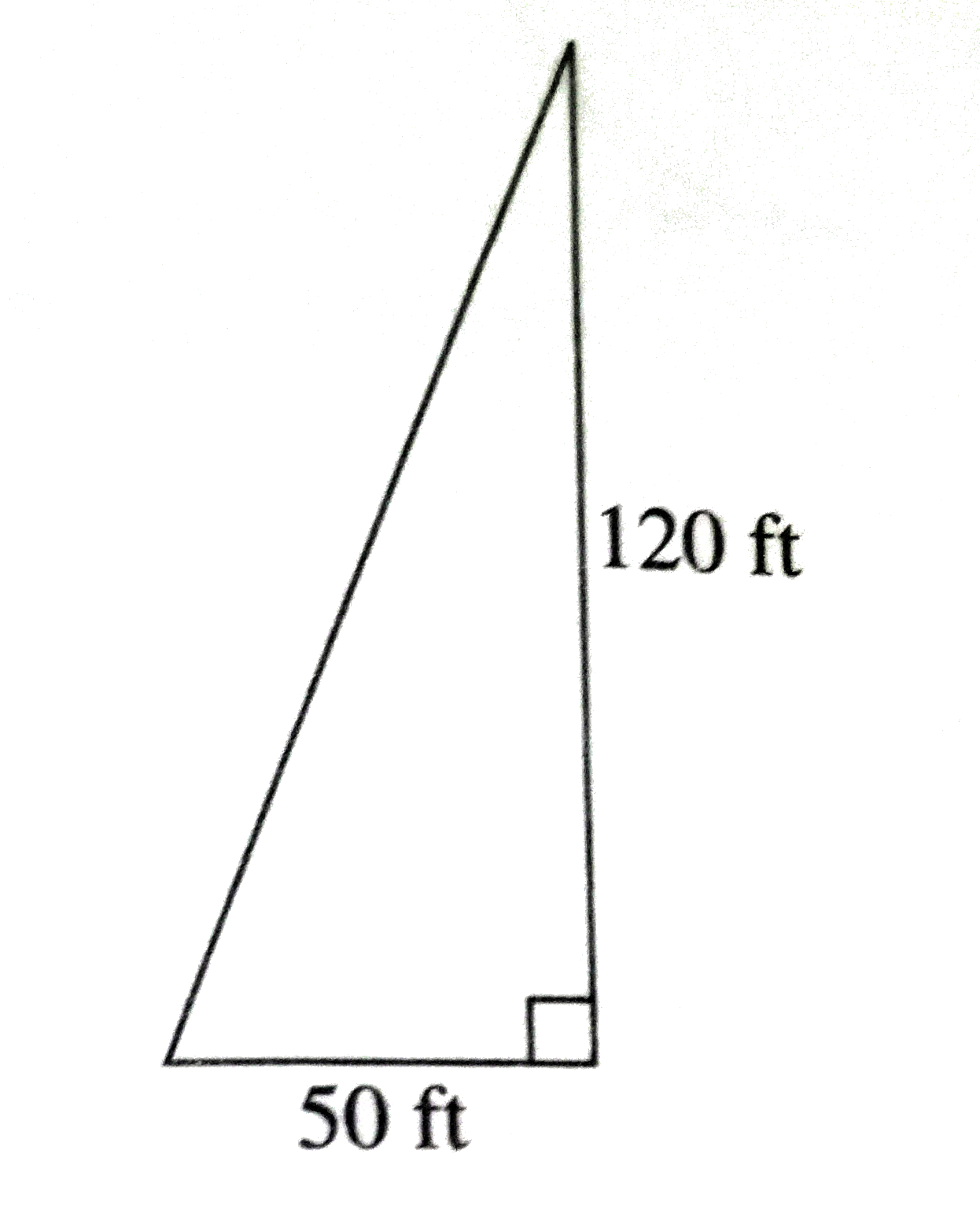

Greg is making a triangular sail for a boat , shaped like a right triangle and shown below .

To determine how much trim to buy for the sail, Greg calculated the sail,s perimeter . What is the sail's perimeter, in feet ?

300

290

275

220

The correct Answer is:A

Topper's Solved these Questions

Similar Questions

A 400m wide river is flowing at a rate of 2.0ms−1. A boat is sailing with a velocity of 10ms−1 with respect to the water, in a direction perpendicular to the river.

(a) Find the time taken by the boat to reach the opposite bank.

(b) How far from the point directly opposite to the starting point does the boat reach the opposite bank ?

( c) In what direction does the boat actually move ?

View SolutionA river 400m wide is flowing at a rate of 2.0m/s. A boat is sailing at a velocity of 10.0m/s with respect to the water In a direction perpendicular to the river.

(a) Find the time taken by the boat to reach the opposite bank.

(b) How far from the point directly opposite to the starting point does the boat reach the opposite bank?

View Solution

Knowledge Check

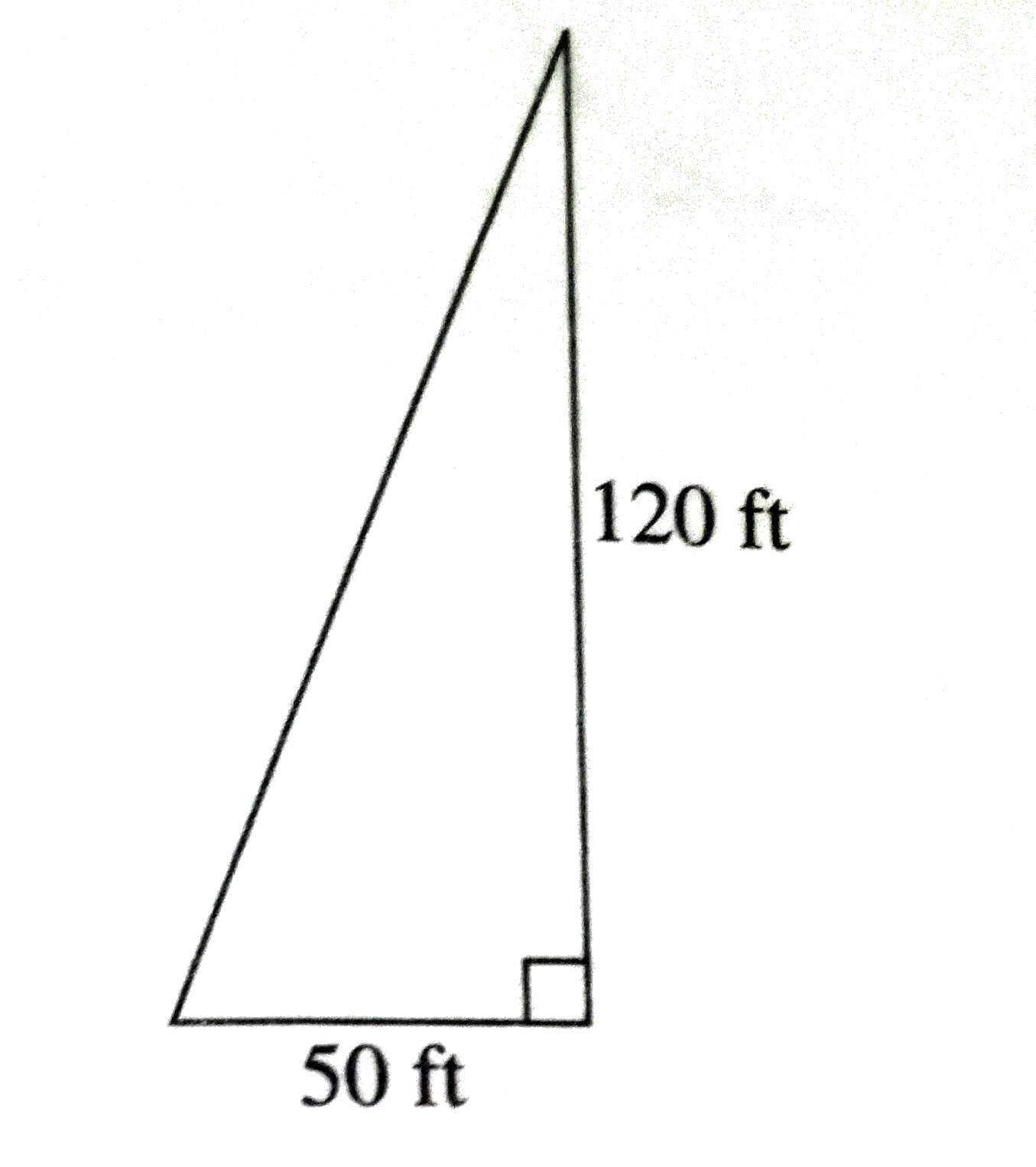

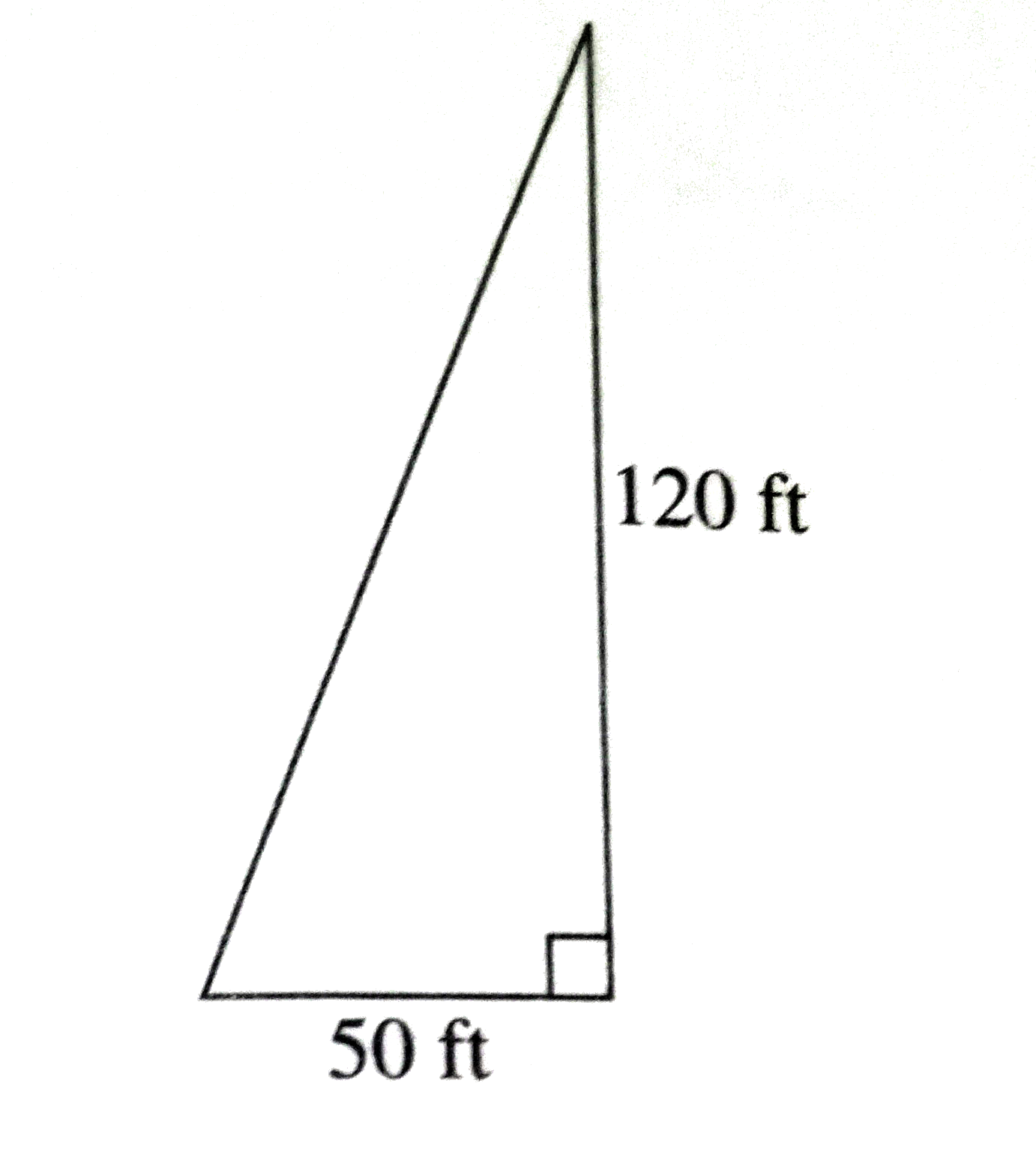

Greg is making a triangular sail for a boat , shaped like a right triangle and shown below .

The angle opposite the 120-foot side measures about 65.2∘. Greg would like to make a second sail. This one will still be a right triangle with a 50-foot side as one leg, but the 120-foot side will be shortened until the angle opposite that side is about 10∘. By about how many feet will Greg need to shorten the 120-foot side ?A9B49C71D111Greg is making a triangular sail for a boat , shaped like a right triangle and shown below .

Sail material costs $8.99 for 150 square feet . If the material can be purchased in any quantity , which of the following is closest to the cost in dollars of the material needed to fill the area of the sail as shown ?A360B280C200D180A grain silo, shown below, is in the shape of cylinder with a half sphere on top . The radius of the base of the cylinder is 10 feet , and the height of the cylindrical part is 60 feet, as marked

The farmer who owns the silo plans to apply a coat of paint to the cylindrical exterior . This does not include the spherical top . A formula for the lateral surface area S of a cylinder with radius r and height h is S=2πrh. if one can of paint covers 300 square feet of surface, what is the least number of cans that the farmer must buy to complete the job ?A10B11C12D13

This passage is adapted from Amy Tan, The Bonesetter’s Daughter. ©2001 by Amy Tan.

At last, Old Widow Lau was done haggling with the driver and we stepped inside Father’s shop. It was north-facing, quite dim inside, and perhaps this was Line why Father did not see us at first. He was busy with a customer, a man who was distinguished-looking, like the scholars of two decades before. The two men were bent over a glass case, discussing the different qualities of inksticks. Big Uncle welcomed us and invited us to be seated. From his formal tone, I knew he did not recognize who we were. So I called his name in a shy voice. And he squinted at me, then laughed and announced our arrival to Little Uncle, who apologized many times for not rushing over sooner to greet us. They rushed us to be seated at one of two tea tables for customers. Old Widow Lau refused their invitation three times, exclaiming that my father and uncles must be too busy for visitors. She made weak efforts to leave. On the fourth insistence, we finally sat. Then Little Uncle brought us hot tea and sweet oranges, as well as bamboo latticework fans with which to cool ourselves. I tried to notice everything so I could later tell GaoLing what I had seen, and tease out her envy. The floors of the shop were of dark wood, polished and clean, no dirty footprints, even though this was during the dustiest part of the summer. And along the walls were display cases made of wood and glass.

The glass was very shiny and not one pane was broken. Within those glass cases were our silk- wrapped boxes, all our hard work. They looked so much nicer than they had in the ink-making studio at Immortal Heart village. I saw that Father had opened several of the boxes. He set sticks and cakes and other shapes on a silk cloth covering a glass case that served as a table on which he and the customer leaned. First he pointed to a stick with a top shaped like a fairy boat and said with graceful importance, “Your writing will flow as smoothly as a keel cutting through a glassy lake.” He picked up a bird shape: “Your mind will soar into the clouds of higher thought.” He waved toward a row of ink cakes embellished with designs of peonies and bamboo: “Your ledgers will blossom into abundance while bamboo surrounds your quiet mind.”

As he said this, Precious Auntie came back into mind. I was remembering how she taught me that everything, even ink, had a purpose and a meaning: Good ink cannot be the quick kind, ready to pour out of a bottle. You can never be an artist if your work comes without effort. That is the problem of modern ink from a bottle. You do not have to think. You simply write what is swimming on the top of your brain. And the top is nothing but pond scum, dead leaves, and mosquito spawn. But when you push an inkstick along an inkstone, you take the first step to cleansing your mind and your heart. You push and you ask yourself, What are my intentions? What is in my heart that matches my mind?

I remembered this, and yet that day in the ink shop, I listened to what Father was saying, and his words became far more important than anything Precious Auntie had thought. “Look here,” Father said to his customer, and I looked. He held up an inkstick and rotated it in the light. “See? It’s the right hue, purple-black, not brown or gray like the cheap brands you might find down the street. And listen to this.” And I heard a sound as clean and pure as a small silver bell. “The high-pitched tone tells you that the soot is very fine, as smooth as the sliding banks of old rivers. And the scent—can you smell the balance of strength and delicacy, the musical notes of the ink’s perfume? Expensive, and everyone who sees you using it will know that it was well worth the high price.” I was very proud to hear Father speak of our family’s ink this way.

Which choice best summarizes the passage?

View SolutionThis passage is adapted from Amy Tan, The Bonesetter’s Daughter. ©2001 by Amy Tan.

At last, Old Widow Lau was done haggling with the driver and we stepped inside Father’s shop. It was north-facing, quite dim inside, and perhaps this was Line why Father did not see us at first. He was busy with a customer, a man who was distinguished-looking, like the scholars of two decades before. The two men were bent over a glass case, discussing the different qualities of inksticks. Big Uncle welcomed us and invited us to be seated. From his formal tone, I knew he did not recognize who we were. So I called his name in a shy voice. And he squinted at me, then laughed and announced our arrival to Little Uncle, who apologized many times for not rushing over sooner to greet us. They rushed us to be seated at one of two tea tables for customers. Old Widow Lau refused their invitation three times, exclaiming that my father and uncles must be too busy for visitors. She made weak efforts to leave. On the fourth insistence, we finally sat. Then Little Uncle brought us hot tea and sweet oranges, as well as bamboo latticework fans with which to cool ourselves. I tried to notice everything so I could later tell GaoLing what I had seen, and tease out her envy. The floors of the shop were of dark wood, polished and clean, no dirty footprints, even though this was during the dustiest part of the summer. And along the walls were display cases made of wood and glass.

The glass was very shiny and not one pane was broken. Within those glass cases were our silk- wrapped boxes, all our hard work. They looked so much nicer than they had in the ink-making studio at Immortal Heart village. I saw that Father had opened several of the boxes. He set sticks and cakes and other shapes on a silk cloth covering a glass case that served as a table on which he and the customer leaned. First he pointed to a stick with a top shaped like a fairy boat and said with graceful importance, “Your writing will flow as smoothly as a keel cutting through a glassy lake.” He picked up a bird shape: “Your mind will soar into the clouds of higher thought.” He waved toward a row of ink cakes embellished with designs of peonies and bamboo: “Your ledgers will blossom into abundance while bamboo surrounds your quiet mind.”

As he said this, Precious Auntie came back into mind. I was remembering how she taught me that everything, even ink, had a purpose and a meaning: Good ink cannot be the quick kind, ready to pour out of a bottle. You can never be an artist if your work comes without effort. That is the problem of modern ink from a bottle. You do not have to think. You simply write what is swimming on the top of your brain. And the top is nothing but pond scum, dead leaves, and mosquito spawn. But when you push an inkstick along an inkstone, you take the first step to cleansing your mind and your heart. You push and you ask yourself, What are my intentions? What is in my heart that matches my mind?

I remembered this, and yet that day in the ink shop, I listened to what Father was saying, and his words became far more important than anything Precious Auntie had thought. “Look here,” Father said to his customer, and I looked. He held up an inkstick and rotated it in the light. “See? It’s the right hue, purple-black, not brown or gray like the cheap brands you might find down the street. And listen to this.” And I heard a sound as clean and pure as a small silver bell. “The high-pitched tone tells you that the soot is very fine, as smooth as the sliding banks of old rivers. And the scent—can you smell the balance of strength and delicacy, the musical notes of the ink’s perfume? Expensive, and everyone who sees you using it will know that it was well worth the high price.” I was very proud to hear Father speak of our family’s ink this way.

Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

View SolutionThis passage is adapted from Amy Tan, The Bonesetter’s Daughter. ©2001 by Amy Tan.

At last, Old Widow Lau was done haggling with the driver and we stepped inside Father’s shop. It was north-facing, quite dim inside, and perhaps this was Line why Father did not see us at first. He was busy with a customer, a man who was distinguished-looking, like the scholars of two decades before. The two men were bent over a glass case, discussing the different qualities of inksticks. Big Uncle welcomed us and invited us to be seated. From his formal tone, I knew he did not recognize who we were. So I called his name in a shy voice. And he squinted at me, then laughed and announced our arrival to Little Uncle, who apologized many times for not rushing over sooner to greet us. They rushed us to be seated at one of two tea tables for customers. Old Widow Lau refused their invitation three times, exclaiming that my father and uncles must be too busy for visitors. She made weak efforts to leave. On the fourth insistence, we finally sat. Then Little Uncle brought us hot tea and sweet oranges, as well as bamboo latticework fans with which to cool ourselves. I tried to notice everything so I could later tell GaoLing what I had seen, and tease out her envy. The floors of the shop were of dark wood, polished and clean, no dirty footprints, even though this was during the dustiest part of the summer. And along the walls were display cases made of wood and glass.

The glass was very shiny and not one pane was broken. Within those glass cases were our silk- wrapped boxes, all our hard work. They looked so much nicer than they had in the ink-making studio at Immortal Heart village. I saw that Father had opened several of the boxes. He set sticks and cakes and other shapes on a silk cloth covering a glass case that served as a table on which he and the customer leaned. First he pointed to a stick with a top shaped like a fairy boat and said with graceful importance, “Your writing will flow as smoothly as a keel cutting through a glassy lake.” He picked up a bird shape: “Your mind will soar into the clouds of higher thought.” He waved toward a row of ink cakes embellished with designs of peonies and bamboo: “Your ledgers will blossom into abundance while bamboo surrounds your quiet mind.”

As he said this, Precious Auntie came back into mind. I was remembering how she taught me that everything, even ink, had a purpose and a meaning: Good ink cannot be the quick kind, ready to pour out of a bottle. You can never be an artist if your work comes without effort. That is the problem of modern ink from a bottle. You do not have to think. You simply write what is swimming on the top of your brain. And the top is nothing but pond scum, dead leaves, and mosquito spawn. But when you push an inkstick along an inkstone, you take the first step to cleansing your mind and your heart. You push and you ask yourself, What are my intentions? What is in my heart that matches my mind?

I remembered this, and yet that day in the ink shop, I listened to what Father was saying, and his words became far more important than anything Precious Auntie had thought. “Look here,” Father said to his customer, and I looked. He held up an inkstick and rotated it in the light. “See? It’s the right hue, purple-black, not brown or gray like the cheap brands you might find down the street. And listen to this.” And I heard a sound as clean and pure as a small silver bell. “The high-pitched tone tells you that the soot is very fine, as smooth as the sliding banks of old rivers. And the scent—can you smell the balance of strength and delicacy, the musical notes of the ink’s perfume? Expensive, and everyone who sees you using it will know that it was well worth the high price.” I was very proud to hear Father speak of our family’s ink this way.

Throughout the passage, the narrator is portrayed as someone who is

View SolutionThis passage is adapted from Amy Tan, The Bonesetter’s Daughter. ©2001 by Amy Tan.

At last, Old Widow Lau was done haggling with the driver and we stepped inside Father’s shop. It was north-facing, quite dim inside, and perhaps this was Line why Father did not see us at first. He was busy with a customer, a man who was distinguished-looking, like the scholars of two decades before. The two men were bent over a glass case, discussing the different qualities of inksticks. Big Uncle welcomed us and invited us to be seated. From his formal tone, I knew he did not recognize who we were. So I called his name in a shy voice. And he squinted at me, then laughed and announced our arrival to Little Uncle, who apologized many times for not rushing over sooner to greet us. They rushed us to be seated at one of two tea tables for customers. Old Widow Lau refused their invitation three times, exclaiming that my father and uncles must be too busy for visitors. She made weak efforts to leave. On the fourth insistence, we finally sat. Then Little Uncle brought us hot tea and sweet oranges, as well as bamboo latticework fans with which to cool ourselves. I tried to notice everything so I could later tell GaoLing what I had seen, and tease out her envy. The floors of the shop were of dark wood, polished and clean, no dirty footprints, even though this was during the dustiest part of the summer. And along the walls were display cases made of wood and glass.

The glass was very shiny and not one pane was broken. Within those glass cases were our silk- wrapped boxes, all our hard work. They looked so much nicer than they had in the ink-making studio at Immortal Heart village. I saw that Father had opened several of the boxes. He set sticks and cakes and other shapes on a silk cloth covering a glass case that served as a table on which he and the customer leaned. First he pointed to a stick with a top shaped like a fairy boat and said with graceful importance, “Your writing will flow as smoothly as a keel cutting through a glassy lake.” He picked up a bird shape: “Your mind will soar into the clouds of higher thought.” He waved toward a row of ink cakes embellished with designs of peonies and bamboo: “Your ledgers will blossom into abundance while bamboo surrounds your quiet mind.”

As he said this, Precious Auntie came back into mind. I was remembering how she taught me that everything, even ink, had a purpose and a meaning: Good ink cannot be the quick kind, ready to pour out of a bottle. You can never be an artist if your work comes without effort. That is the problem of modern ink from a bottle. You do not have to think. You simply write what is swimming on the top of your brain. And the top is nothing but pond scum, dead leaves, and mosquito spawn. But when you push an inkstick along an inkstone, you take the first step to cleansing your mind and your heart. You push and you ask yourself, What are my intentions? What is in my heart that matches my mind?

I remembered this, and yet that day in the ink shop, I listened to what Father was saying, and his words became far more important than anything Precious Auntie had thought. “Look here,” Father said to his customer, and I looked. He held up an inkstick and rotated it in the light. “See? It’s the right hue, purple-black, not brown or gray like the cheap brands you might find down the street. And listen to this.” And I heard a sound as clean and pure as a small silver bell. “The high-pitched tone tells you that the soot is very fine, as smooth as the sliding banks of old rivers. And the scent—can you smell the balance of strength and delicacy, the musical notes of the ink’s perfume? Expensive, and everyone who sees you using it will know that it was well worth the high price.” I was very proud to hear Father speak of our family’s ink this way.

A main theme of the passage is that

View SolutionThis passage is adapted from Amy Tan, The Bonesetter’s Daughter. ©2001 by Amy Tan.

At last, Old Widow Lau was done haggling with the driver and we stepped inside Father’s shop. It was north-facing, quite dim inside, and perhaps this was Line why Father did not see us at first. He was busy with a customer, a man who was distinguished-looking, like the scholars of two decades before. The two men were bent over a glass case, discussing the different qualities of inksticks. Big Uncle welcomed us and invited us to be seated. From his formal tone, I knew he did not recognize who we were. So I called his name in a shy voice. And he squinted at me, then laughed and announced our arrival to Little Uncle, who apologized many times for not rushing over sooner to greet us. They rushed us to be seated at one of two tea tables for customers. Old Widow Lau refused their invitation three times, exclaiming that my father and uncles must be too busy for visitors. She made weak efforts to leave. On the fourth insistence, we finally sat. Then Little Uncle brought us hot tea and sweet oranges, as well as bamboo latticework fans with which to cool ourselves. I tried to notice everything so I could later tell GaoLing what I had seen, and tease out her envy. The floors of the shop were of dark wood, polished and clean, no dirty footprints, even though this was during the dustiest part of the summer. And along the walls were display cases made of wood and glass.

The glass was very shiny and not one pane was broken. Within those glass cases were our silk- wrapped boxes, all our hard work. They looked so much nicer than they had in the ink-making studio at Immortal Heart village. I saw that Father had opened several of the boxes. He set sticks and cakes and other shapes on a silk cloth covering a glass case that served as a table on which he and the customer leaned. First he pointed to a stick with a top shaped like a fairy boat and said with graceful importance, “Your writing will flow as smoothly as a keel cutting through a glassy lake.” He picked up a bird shape: “Your mind will soar into the clouds of higher thought.” He waved toward a row of ink cakes embellished with designs of peonies and bamboo: “Your ledgers will blossom into abundance while bamboo surrounds your quiet mind.”

As he said this, Precious Auntie came back into mind. I was remembering how she taught me that everything, even ink, had a purpose and a meaning: Good ink cannot be the quick kind, ready to pour out of a bottle. You can never be an artist if your work comes without effort. That is the problem of modern ink from a bottle. You do not have to think. You simply write what is swimming on the top of your brain. And the top is nothing but pond scum, dead leaves, and mosquito spawn. But when you push an inkstick along an inkstone, you take the first step to cleansing your mind and your heart. You push and you ask yourself, What are my intentions? What is in my heart that matches my mind?

I remembered this, and yet that day in the ink shop, I listened to what Father was saying, and his words became far more important than anything Precious Auntie had thought. “Look here,” Father said to his customer, and I looked. He held up an inkstick and rotated it in the light. “See? It’s the right hue, purple-black, not brown or gray like the cheap brands you might find down the street. And listen to this.” And I heard a sound as clean and pure as a small silver bell. “The high-pitched tone tells you that the soot is very fine, as smooth as the sliding banks of old rivers. And the scent—can you smell the balance of strength and delicacy, the musical notes of the ink’s perfume? Expensive, and everyone who sees you using it will know that it was well worth the high price.” I was very proud to hear Father speak of our family’s ink this way.

The narrator indicates that the contrast between the ink-making studio at Immortal Heart village and her family’s ink shop is that the ink shop

View Solution