Do you think that reproductive health in our country has improved in the past 50 years? If yes, mention some such areas of improvement.

Step-by-Step Solution:

1. Introduction to Reproductive Health Improvement:

- Begin by acknowledging the question regarding the improvement of reproductive health in the country over the past 50 years. State that there has indeed been progress in several areas.

2. Increased Awareness:

- Discuss the increase in public awareness regarding reproductive health issues, including sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and other sex-related matters. Highlight that people are now more informed compared to previous decades.

3. Enhanced Medical Facilities:

- Mention the significant improvements in medical facilities and healthcare services. Emphasize the advancements in prenatal and postnatal care, which have contributed to a reduction in maternal and infant mortality rates.

4. Family Planning Initiatives:

- Explain how there has been a shift towards better family planning practices. More couples are now engaging in family planning, leading to more informed decisions about childbearing.

5. Improved Detection and Treatment of STDs:

- Highlight advancements in the detection and treatment of STDs. Explain how these improvements have led to a decrease in mortality rates associated with these diseases.

6. Conclusion:

- Conclude by summarizing that while there are still areas needing improvement, the overall reproductive health landscape in the country has seen significant positive changes over the past 50 years.

- Begin by acknowledging the question regarding the improvement of reproductive health in the country over the past 50 years. State that there has indeed been progress in several areas.

- Discuss the increase in public awareness regarding reproductive health issues, including sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and other sex-related matters. Highlight that people are now more informed compared to previous decades.

- Mention the significant improvements in medical facilities and healthcare services. Emphasize the advancements in prenatal and postnatal care, which have contributed to a reduction in maternal and infant mortality rates.

- Explain how there has been a shift towards better family planning practices. More couples are now engaging in family planning, leading to more informed decisions about childbearing.

- Highlight advancements in the detection and treatment of STDs. Explain how these improvements have led to a decrease in mortality rates associated with these diseases.

- Conclude by summarizing that while there are still areas needing improvement, the overall reproductive health landscape in the country has seen significant positive changes over the past 50 years.

Topper's Solved these Questions

Similar Questions

List four points of significance of reproductive health in a society. Name any two areas

related to reproductive health which have improved over the past 50 years in our

country.

View SolutionIf you have been consulted by rapidly growing city authorities to improve air quality, which is deteriorated in the past ten years, your first suggestion is to

View Solution

Knowledge Check

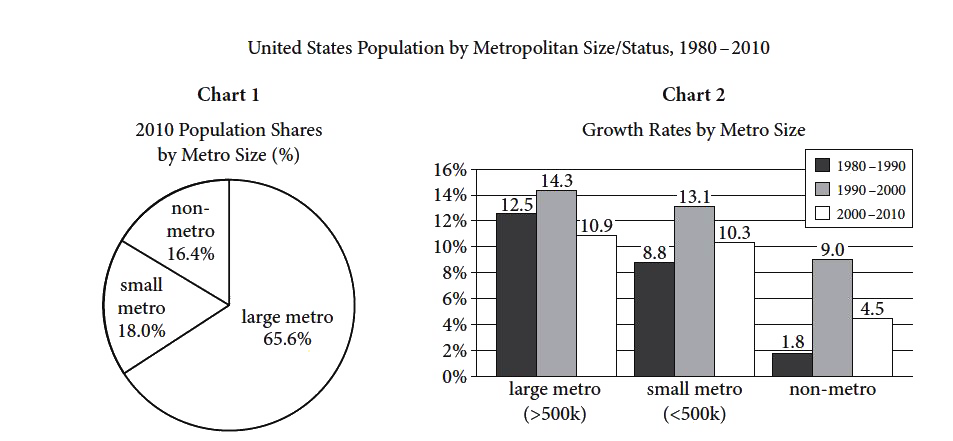

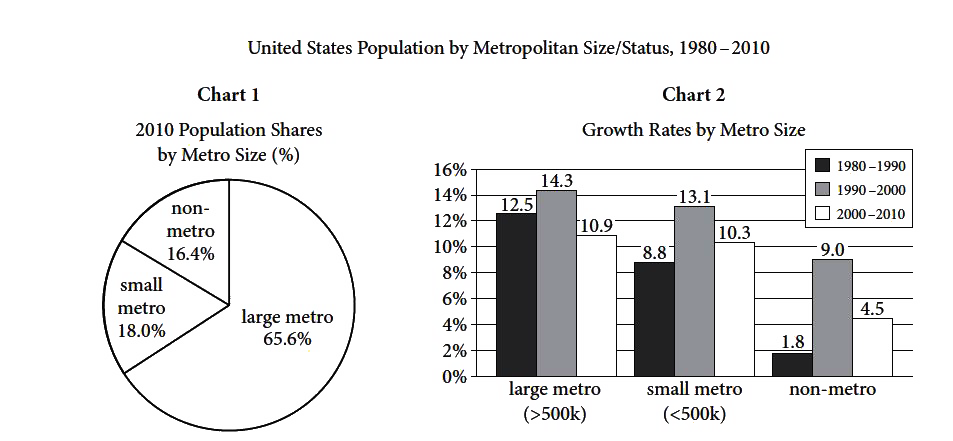

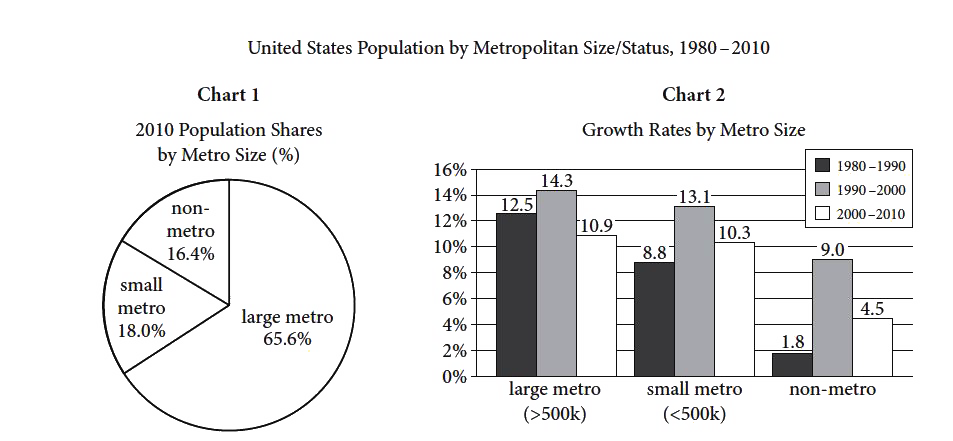

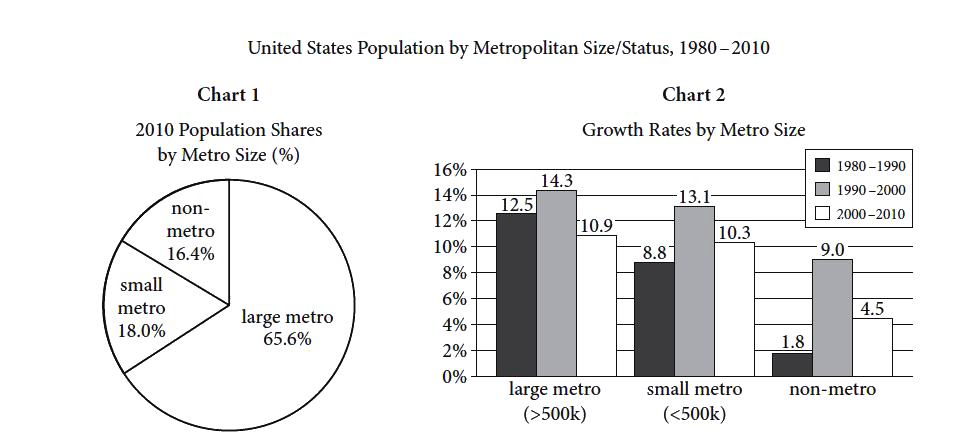

We are not witnessing the abandonment of the suburbs, or a movement of millions of people back to the city all at once. The 2010 census certainly did not turn up evidence of a middle-class stampede to the nation’s cities. The news was mixed: Some of the larger cities on the East Coast tended to gain population, albeit in small increments. Those in the Midwest, including Chicago, tended to lose substantial numbers. The cities that showed gains in overall population during the entire decade tended to be in the South and Southwest. But when it comes to measuring demographic inversion, raw census numbers are an ineffective blunt instrument. A closer look at the results shows that the most powerful demographic events of the past decade were the movement of African Americans out of central cities (180,000 of them in Chicago alone) and the settlement of immigrant groups in suburbs, often ones many miles distant from downtown.

Central-city areas that gained affluent residents in the first part of the decade maintained that population in the recession years from 2007 to 2009. They also, according to a 2011 study by Brookings, uffered considerably less from increased unemployment than the suburbs did. Not many young professionals moved to new downtown condos in the recession years because few such residences were being built. But there is no reason to believe that the demographic trends prevailing prior to the construction bust will not resume once that bust is over. It is important to remember that demographic inversion is not a proxy for population growth, it can occur in cities that are growing, those whose numbers are flat, and even in those undergoing a modest decline in size.

America’s major cities face enormous fiscal problems, many of them the result of public pension obligations they incurred in the more prosperous years of the past two decades. Some, Chicago rominent among them, simply are not producing enough revenue to support the level of public services to which most of the citizens have grown to feel entitled. How the cities are going to solve thisproblem, I do not know. What I do know is that if fiscal crisis were going to drive affluent professionals out of central cities, it would have done so by now. There is no evidence that it has. The truth is that we are living at a moment in which the massive outward migration of the affluent that characterized the second half of the twentieth century is coming to an end. And we need to adjust our perceptions of cities, suburbs, and urban mobility as a result.

Much of our perspe ctive on the process of metropolitan settlement dates, whether we realize it or not, from a paper written in 1925 by the University of Chicago sociologist Ernest W. Burgess. It was Burgess who defined four urban/suburban zones of settlement: a central business district, an area of manufacturing just beyond it, then a residential area inhabited by the industrial and immigrant working class, and finally an outer enclave of single-family dwellings. Burgess was right about the urban America of 1925, he was right about the urban America of 1974. Virtually every city in the country had a downtown, where the commercial life of the metropolis was conducted, it had a factory district just beyond, it had districts of working-class residences just beyond that, and it had residential suburbs for the wealthy and the upper middle class at the far end of the continuum. As a family moved up the economic ladder, it also moved outward from crowded working-class districts to more spacious apartments and, eventually, to a suburban home. The suburbs of Burgess’s time bore little resemblance to those at the end of the twentieth century, but the theory still essentially worked. People moved ahead in life by moving farther out.

But in the past decade, in quite a few places, this model has ceased to describe reality. There are still downtown commercial districts, but there are no factory districts lying next to them. There are scarcely any factories at all. These close-in parts of the city, whose few residents Burgess described as dwelling in “submerged regions of poverty, degradation and disease,” are increasingly the preserve of the affluent who work in the commercial core. And just as crucially newcomers to America are not settling on the inside and accumulating the resources to move out, they are living in the suburbs from day one.

In line 34, “flat” is closest in meaning toAstatic.Bdeflated.Cfeatureless.Dobscure.We are not witnessing the abandonment of the suburbs, or a movement of millions of people back to the city all at once. The 2010 census certainly did not turn up evidence of a middle-class stampede to the nation’s cities. The news was mixed: Some of the larger cities on the East Coast tended to gain population, albeit in small increments. Those in the Midwest, including Chicago, tended to lose substantial numbers. The cities that showed gains in overall population during the entire decade tended to be in the South and Southwest. But when it comes to measuring demographic inversion, raw census numbers are an ineffective blunt instrument. A closer look at the results shows that the most powerful demographic events of the past decade were the movement of African Americans out of central cities (180,000 of them in Chicago alone) and the settlement of immigrant groups in suburbs, often ones many miles distant from downtown.

Central-city areas that gained affluent residents in the first part of the decade maintained that population in the recession years from 2007 to 2009. They also, according to a 2011 study by Brookings, uffered considerably less from increased unemployment than the suburbs did. Not many young professionals moved to new downtown condos in the recession years because few such residences were being built. But there is no reason to believe that the demographic trends prevailing prior to the construction bust will not resume once that bust is over. It is important to remember that demographic inversion is not a proxy for population growth, it can occur in cities that are growing, those whose numbers are flat, and even in those undergoing a modest decline in size.

America’s major cities face enormous fiscal problems, many of them the result of public pension obligations they incurred in the more prosperous years of the past two decades. Some, Chicago rominent among them, simply are not producing enough revenue to support the level of public services to which most of the citizens have grown to feel entitled. How the cities are going to solve thisproblem, I do not know. What I do know is that if fiscal crisis were going to drive affluent professionals out of central cities, it would have done so by now. There is no evidence that it has. The truth is that we are living at a moment in which the massive outward migration of the affluent that characterized the second half of the twentieth century is coming to an end. And we need to adjust our perceptions of cities, suburbs, and urban mobility as a result.

Much of our perspe ctive on the process of metropolitan settlement dates, whether we realize it or not, from a paper written in 1925 by the University of Chicago sociologist Ernest W. Burgess. It was Burgess who defined four urban/suburban zones of settlement: a central business district, an area of manufacturing just beyond it, then a residential area inhabited by the industrial and immigrant working class, and finally an outer enclave of single-family dwellings. Burgess was right about the urban America of 1925, he was right about the urban America of 1974. Virtually every city in the country had a downtown, where the commercial life of the metropolis was conducted, it had a factory district just beyond, it had districts of working-class residences just beyond that, and it had residential suburbs for the wealthy and the upper middle class at the far end of the continuum. As a family moved up the economic ladder, it also moved outward from crowded working-class districts to more spacious apartments and, eventually, to a suburban home. The suburbs of Burgess’s time bore little resemblance to those at the end of the twentieth century, but the theory still essentially worked. People moved ahead in life by moving farther out.

But in the past decade, in quite a few places, this model has ceased to describe reality. There are still downtown commercial districts, but there are no factory districts lying next to them. There are scarcely any factories at all. These close-in parts of the city, whose few residents Burgess described as dwelling in “submerged regions of poverty, degradation and disease,” are increasingly the preserve of the affluent who work in the commercial core. And just as crucially newcomers to America are not settling on the inside and accumulating the resources to move out, they are living in the suburbs from day one.

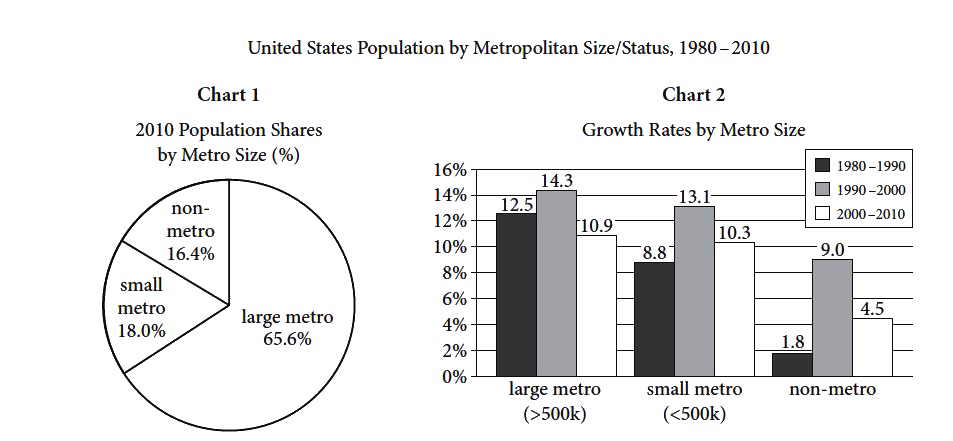

Which choice best summarizes the first paragraph of the passage (lines 1-35)?AThe 2010 census demonstrated a sizeable growth in the number of middle-class families moving into inner cities.BThe 2010 census is not a reliable instrument for measuring population trends in American cities.CPopulation growth and demographic inversion are distinct phenomena, and demographic inversion is evident in many American cities.DPopulation growth in American cities has been increasing since roughly 2000, while suburban populations have decreased.We are not witnessing the abandonment of the suburbs, or a movement of millions of people back to the city all at once. The 2010 census certainly did not turn up evidence of a middle-class stampede to the nation’s cities. The news was mixed: Some of the larger cities on the East Coast tended to gain population, albeit in small increments. Those in the Midwest, including Chicago, tended to lose substantial numbers. The cities that showed gains in overall population during the entire decade tended to be in the South and Southwest. But when it comes to measuring demographic inversion, raw census numbers are an ineffective blunt instrument. A closer look at the results shows that the most powerful demographic events of the past decade were the movement of African Americans out of central cities (180,000 of them in Chicago alone) and the settlement of immigrant groups in suburbs, often ones many miles distant from downtown.

Central-city areas that gained affluent residents in the first part of the decade maintained that population in the recession years from 2007 to 2009. They also, according to a 2011 study by Brookings, uffered considerably less from increased unemployment than the suburbs did. Not many young professionals moved to new downtown condos in the recession years because few such residences were being built. But there is no reason to believe that the demographic trends prevailing prior to the construction bust will not resume once that bust is over. It is important to remember that demographic inversion is not a proxy for population growth, it can occur in cities that are growing, those whose numbers are flat, and even in those undergoing a modest decline in size.

America’s major cities face enormous fiscal problems, many of them the result of public pension obligations they incurred in the more prosperous years of the past two decades. Some, Chicago rominent among them, simply are not producing enough revenue to support the level of public services to which most of the citizens have grown to feel entitled. How the cities are going to solve thisproblem, I do not know. What I do know is that if fiscal crisis were going to drive affluent professionals out of central cities, it would have done so by now. There is no evidence that it has. The truth is that we are living at a moment in which the massive outward migration of the affluent that characterized the second half of the twentieth century is coming to an end. And we need to adjust our perceptions of cities, suburbs, and urban mobility as a result.

Much of our perspe ctive on the process of metropolitan settlement dates, whether we realize it or not, from a paper written in 1925 by the University of Chicago sociologist Ernest W. Burgess. It was Burgess who defined four urban/suburban zones of settlement: a central business district, an area of manufacturing just beyond it, then a residential area inhabited by the industrial and immigrant working class, and finally an outer enclave of single-family dwellings. Burgess was right about the urban America of 1925, he was right about the urban America of 1974. Virtually every city in the country had a downtown, where the commercial life of the metropolis was conducted, it had a factory district just beyond, it had districts of working-class residences just beyond that, and it had residential suburbs for the wealthy and the upper middle class at the far end of the continuum. As a family moved up the economic ladder, it also moved outward from crowded working-class districts to more spacious apartments and, eventually, to a suburban home. The suburbs of Burgess’s time bore little resemblance to those at the end of the twentieth century, but the theory still essentially worked. People moved ahead in life by moving farther out.

But in the past decade, in quite a few places, this model has ceased to describe reality. There are still downtown commercial districts, but there are no factory districts lying next to them. There are scarcely any factories at all. These close-in parts of the city, whose few residents Burgess described as dwelling in “submerged regions of poverty, degradation and disease,” are increasingly the preserve of the affluent who work in the commercial core. And just as crucially newcomers to America are not settling on the inside and accumulating the resources to move out, they are living in the suburbs from day one.

According to the passage, members of which group moved away from central-city areas in large numbers in the early 2000s?AThe unemployedBImmigrantsCYoung professionalsDAfrican Americans

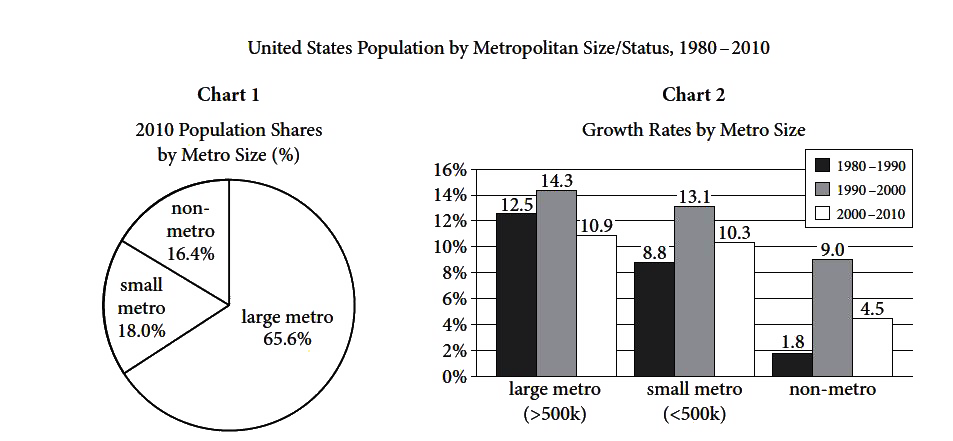

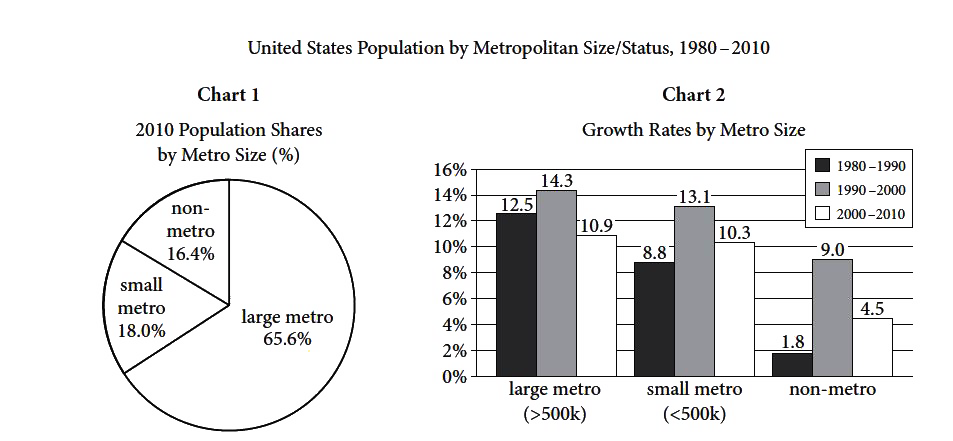

We are not witnessing the abandonment of the suburbs, or a movement of millions of people back to the city all at once. The 2010 census certainly did not turn up evidence of a middle-class stampede to the nation’s cities. The news was mixed: Some of the larger cities on the East Coast tended to gain population, albeit in small increments. Those in the Midwest, including Chicago, tended to lose substantial numbers. The cities that showed gains in overall population during the entire decade tended to be in the South and Southwest. But when it comes to measuring demographic inversion, raw census numbers are an ineffective blunt instrument. A closer look at the results shows that the most powerful demographic events of the past decade were the movement of African Americans out of central cities (180,000 of them in Chicago alone) and the settlement of immigrant groups in suburbs, often ones many miles distant from downtown.

Central-city areas that gained affluent residents in the first part of the decade maintained that population in the recession years from 2007 to 2009. They also, according to a 2011 study by Brookings, uffered considerably less from increased unemployment than the suburbs did. Not many young professionals moved to new downtown condos in the recession years because few such residences were being built. But there is no reason to believe that the demographic trends prevailing prior to the construction bust will not resume once that bust is over. It is important to remember that demographic inversion is not a proxy for population growth, it can occur in cities that are growing, those whose numbers are flat, and even in those undergoing a modest decline in size.

America’s major cities face enormous fiscal problems, many of them the result of public pension obligations they incurred in the more prosperous years of the past two decades. Some, Chicago rominent among them, simply are not producing enough revenue to support the level of public services to which most of the citizens have grown to feel entitled. How the cities are going to solve thisproblem, I do not know. What I do know is that if fiscal crisis were going to drive affluent professionals out of central cities, it would have done so by now. There is no evidence that it has. The truth is that we are living at a moment in which the massive outward migration of the affluent that characterized the second half of the twentieth century is coming to an end. And we need to adjust our perceptions of cities, suburbs, and urban mobility as a result.

Much of our perspe ctive on the process of metropolitan settlement dates, whether we realize it or not, from a paper written in 1925 by the University of Chicago sociologist Ernest W. Burgess. It was Burgess who defined four urban/suburban zones of settlement: a central business district, an area of manufacturing just beyond it, then a residential area inhabited by the industrial and immigrant working class, and finally an outer enclave of single-family dwellings. Burgess was right about the urban America of 1925, he was right about the urban America of 1974. Virtually every city in the country had a downtown, where the commercial life of the metropolis was conducted, it had a factory district just beyond, it had districts of working-class residences just beyond that, and it had residential suburbs for the wealthy and the upper middle class at the far end of the continuum. As a family moved up the economic ladder, it also moved outward from crowded working-class districts to more spacious apartments and, eventually, to a suburban home. The suburbs of Burgess’s time bore little resemblance to those at the end of the twentieth century, but the theory still essentially worked. People moved ahead in life by moving farther out.

But in the past decade, in quite a few places, this model has ceased to describe reality. There are still downtown commercial districts, but there are no factory districts lying next to them. There are scarcely any factories at all. These close-in parts of the city, whose few residents Burgess described as dwelling in “submerged regions of poverty, degradation and disease,” are increasingly the preserve of the affluent who work in the commercial core. And just as crucially newcomers to America are not settling on the inside and accumulating the resources to move out, they are living in the suburbs from day one.

According to the passage, which choice best describes the current financial situation in many major American cities?

View SolutionWe are not witnessing the abandonment of the suburbs, or a movement of millions of people back to the city all at once. The 2010 census certainly did not turn up evidence of a middle-class stampede to the nation’s cities. The news was mixed: Some of the larger cities on the East Coast tended to gain population, albeit in small increments. Those in the Midwest, including Chicago, tended to lose substantial numbers. The cities that showed gains in overall population during the entire decade tended to be in the South and Southwest. But when it comes to measuring demographic inversion, raw census numbers are an ineffective blunt instrument. A closer look at the results shows that the most powerful demographic events of the past decade were the movement of African Americans out of central cities (180,000 of them in Chicago alone) and the settlement of immigrant groups in suburbs, often ones many miles distant from downtown.

Central-city areas that gained affluent residents in the first part of the decade maintained that population in the recession years from 2007 to 2009. They also, according to a 2011 study by Brookings, uffered considerably less from increased unemployment than the suburbs did. Not many young professionals moved to new downtown condos in the recession years because few such residences were being built. But there is no reason to believe that the demographic trends prevailing prior to the construction bust will not resume once that bust is over. It is important to remember that demographic inversion is not a proxy for population growth, it can occur in cities that are growing, those whose numbers are flat, and even in those undergoing a modest decline in size.

America’s major cities face enormous fiscal problems, many of them the result of public pension obligations they incurred in the more prosperous years of the past two decades. Some, Chicago rominent among them, simply are not producing enough revenue to support the level of public services to which most of the citizens have grown to feel entitled. How the cities are going to solve thisproblem, I do not know. What I do know is that if fiscal crisis were going to drive affluent professionals out of central cities, it would have done so by now. There is no evidence that it has. The truth is that we are living at a moment in which the massive outward migration of the affluent that characterized the second half of the twentieth century is coming to an end. And we need to adjust our perceptions of cities, suburbs, and urban mobility as a result.

Much of our perspe ctive on the process of metropolitan settlement dates, whether we realize it or not, from a paper written in 1925 by the University of Chicago sociologist Ernest W. Burgess. It was Burgess who defined four urban/suburban zones of settlement: a central business district, an area of manufacturing just beyond it, then a residential area inhabited by the industrial and immigrant working class, and finally an outer enclave of single-family dwellings. Burgess was right about the urban America of 1925, he was right about the urban America of 1974. Virtually every city in the country had a downtown, where the commercial life of the metropolis was conducted, it had a factory district just beyond, it had districts of working-class residences just beyond that, and it had residential suburbs for the wealthy and the upper middle class at the far end of the continuum. As a family moved up the economic ladder, it also moved outward from crowded working-class districts to more spacious apartments and, eventually, to a suburban home. The suburbs of Burgess’s time bore little resemblance to those at the end of the twentieth century, but the theory still essentially worked. People moved ahead in life by moving farther out.

But in the past decade, in quite a few places, this model has ceased to describe reality. There are still downtown commercial districts, but there are no factory districts lying next to them. There are scarcely any factories at all. These close-in parts of the city, whose few residents Burgess described as dwelling in “submerged regions of poverty, degradation and disease,” are increasingly the preserve of the affluent who work in the commercial core. And just as crucially newcomers to America are not settling on the inside and accumulating the resources to move out, they are living in the suburbs from day one.

Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

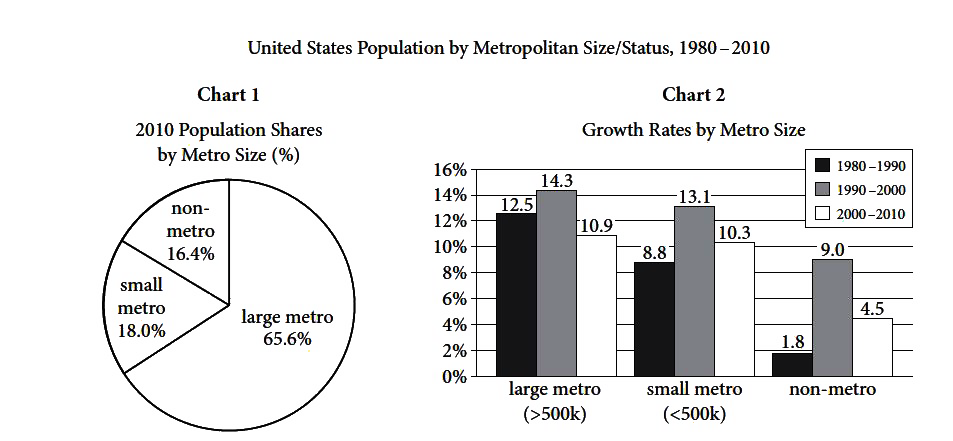

View SolutionWe are not witnessing the abandonment of the suburbs, or a movement of millions of people back to the city all at once. The 2010 census certainly did not turn up evidence of a middle-class stampede to the nation’s cities. The news was mixed: Some of the larger cities on the East Coast tended to gain population, albeit in small increments. Those in the Midwest, including Chicago, tended to lose substantial numbers. The cities that showed gains in overall population during the entire decade tended to be in the South and Southwest. But when it comes to measuring demographic inversion, raw census numbers are an ineffective blunt instrument. A closer look at the results shows that the most powerful demographic events of the past decade were the movement of African Americans out of central cities (180,000 of them in Chicago alone) and the settlement of immigrant groups in suburbs, often ones many miles distant from downtown.

Central-city areas that gained affluent residents in the first part of the decade maintained that population in the recession years from 2007 to 2009. They also, according to a 2011 study by Brookings, uffered considerably less from increased unemployment than the suburbs did. Not many young professionals moved to new downtown condos in the recession years because few such residences were being built. But there is no reason to believe that the demographic trends prevailing prior to the construction bust will not resume once that bust is over. It is important to remember that demographic inversion is not a proxy for population growth, it can occur in cities that are growing, those whose numbers are flat, and even in those undergoing a modest decline in size.

America’s major cities face enormous fiscal problems, many of them the result of public pension obligations they incurred in the more prosperous years of the past two decades. Some, Chicago rominent among them, simply are not producing enough revenue to support the level of public services to which most of the citizens have grown to feel entitled. How the cities are going to solve thisproblem, I do not know. What I do know is that if fiscal crisis were going to drive affluent professionals out of central cities, it would have done so by now. There is no evidence that it has. The truth is that we are living at a moment in which the massive outward migration of the affluent that characterized the second half of the twentieth century is coming to an end. And we need to adjust our perceptions of cities, suburbs, and urban mobility as a result.

Much of our perspe ctive on the process of metropolitan settlement dates, whether we realize it or not, from a paper written in 1925 by the University of Chicago sociologist Ernest W. Burgess. It was Burgess who defined four urban/suburban zones of settlement: a central business district, an area of manufacturing just beyond it, then a residential area inhabited by the industrial and immigrant working class, and finally an outer enclave of single-family dwellings. Burgess was right about the urban America of 1925, he was right about the urban America of 1974. Virtually every city in the country had a downtown, where the commercial life of the metropolis was conducted, it had a factory district just beyond, it had districts of working-class residences just beyond that, and it had residential suburbs for the wealthy and the upper middle class at the far end of the continuum. As a family moved up the economic ladder, it also moved outward from crowded working-class districts to more spacious apartments and, eventually, to a suburban home. The suburbs of Burgess’s time bore little resemblance to those at the end of the twentieth century, but the theory still essentially worked. People moved ahead in life by moving farther out.

But in the past decade, in quite a few places, this model has ceased to describe reality. There are still downtown commercial districts, but there are no factory districts lying next to them. There are scarcely any factories at all. These close-in parts of the city, whose few residents Burgess described as dwelling in “submerged regions of poverty, degradation and disease,” are increasingly the preserve of the affluent who work in the commercial core. And just as crucially newcomers to America are not settling on the inside and accumulating the resources to move out, they are living in the suburbs from day one.

The passage implies that American cities in 1974

View SolutionWe are not witnessing the abandonment of the suburbs, or a movement of millions of people back to the city all at once. The 2010 census certainly did not turn up evidence of a middle-class stampede to the nation’s cities. The news was mixed: Some of the larger cities on the East Coast tended to gain population, albeit in small increments. Those in the Midwest, including Chicago, tended to lose substantial numbers. The cities that showed gains in overall population during the entire decade tended to be in the South and Southwest. But when it comes to measuring demographic inversion, raw census numbers are an ineffective blunt instrument. A closer look at the results shows that the most powerful demographic events of the past decade were the movement of African Americans out of central cities (180,000 of them in Chicago alone) and the settlement of immigrant groups in suburbs, often ones many miles distant from downtown.

Central-city areas that gained affluent residents in the first part of the decade maintained that population in the recession years from 2007 to 2009. They also, according to a 2011 study by Brookings, uffered considerably less from increased unemployment than the suburbs did. Not many young professionals moved to new downtown condos in the recession years because few such residences were being built. But there is no reason to believe that the demographic trends prevailing prior to the construction bust will not resume once that bust is over. It is important to remember that demographic inversion is not a proxy for population growth, it can occur in cities that are growing, those whose numbers are flat, and even in those undergoing a modest decline in size.

America’s major cities face enormous fiscal problems, many of them the result of public pension obligations they incurred in the more prosperous years of the past two decades. Some, Chicago rominent among them, simply are not producing enough revenue to support the level of public services to which most of the citizens have grown to feel entitled. How the cities are going to solve thisproblem, I do not know. What I do know is that if fiscal crisis were going to drive affluent professionals out of central cities, it would have done so by now. There is no evidence that it has. The truth is that we are living at a moment in which the massive outward migration of the affluent that characterized the second half of the twentieth century is coming to an end. And we need to adjust our perceptions of cities, suburbs, and urban mobility as a result.

Much of our perspe ctive on the process of metropolitan settlement dates, whether we realize it or not, from a paper written in 1925 by the University of Chicago sociologist Ernest W. Burgess. It was Burgess who defined four urban/suburban zones of settlement: a central business district, an area of manufacturing just beyond it, then a residential area inhabited by the industrial and immigrant working class, and finally an outer enclave of single-family dwellings. Burgess was right about the urban America of 1925, he was right about the urban America of 1974. Virtually every city in the country had a downtown, where the commercial life of the metropolis was conducted, it had a factory district just beyond, it had districts of working-class residences just beyond that, and it had residential suburbs for the wealthy and the upper middle class at the far end of the continuum. As a family moved up the economic ladder, it also moved outward from crowded working-class districts to more spacious apartments and, eventually, to a suburban home. The suburbs of Burgess’s time bore little resemblance to those at the end of the twentieth century, but the theory still essentially worked. People moved ahead in life by moving farther out.

But in the past decade, in quite a few places, this model has ceased to describe reality. There are still downtown commercial districts, but there are no factory districts lying next to them. There are scarcely any factories at all. These close-in parts of the city, whose few residents Burgess described as dwelling in “submerged regions of poverty, degradation and disease,” are increasingly the preserve of the affluent who work in the commercial core. And just as crucially newcomers to America are not settling on the inside and accumulating the resources to move out, they are living in the suburbs from day one.

Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

View SolutionWe are not witnessing the abandonment of the suburbs, or a movement of millions of people back to the city all at once. The 2010 census certainly did not turn up evidence of a middle-class stampede to the nation’s cities. The news was mixed: Some of the larger cities on the East Coast tended to gain population, albeit in small increments. Those in the Midwest, including Chicago, tended to lose substantial numbers. The cities that showed gains in overall population during the entire decade tended to be in the South and Southwest. But when it comes to measuring demographic inversion, raw census numbers are an ineffective blunt instrument. A closer look at the results shows that the most powerful demographic events of the past decade were the movement of African Americans out of central cities (180,000 of them in Chicago alone) and the settlement of immigrant groups in suburbs, often ones many miles distant from downtown.

Central-city areas that gained affluent residents in the first part of the decade maintained that population in the recession years from 2007 to 2009. They also, according to a 2011 study by Brookings, uffered considerably less from increased unemployment than the suburbs did. Not many young professionals moved to new downtown condos in the recession years because few such residences were being built. But there is no reason to believe that the demographic trends prevailing prior to the construction bust will not resume once that bust is over. It is important to remember that demographic inversion is not a proxy for population growth, it can occur in cities that are growing, those whose numbers are flat, and even in those undergoing a modest decline in size.

America’s major cities face enormous fiscal problems, many of them the result of public pension obligations they incurred in the more prosperous years of the past two decades. Some, Chicago rominent among them, simply are not producing enough revenue to support the level of public services to which most of the citizens have grown to feel entitled. How the cities are going to solve thisproblem, I do not know. What I do know is that if fiscal crisis were going to drive affluent professionals out of central cities, it would have done so by now. There is no evidence that it has. The truth is that we are living at a moment in which the massive outward migration of the affluent that characterized the second half of the twentieth century is coming to an end. And we need to adjust our perceptions of cities, suburbs, and urban mobility as a result.

Much of our perspe ctive on the process of metropolitan settlement dates, whether we realize it or not, from a paper written in 1925 by the University of Chicago sociologist Ernest W. Burgess. It was Burgess who defined four urban/suburban zones of settlement: a central business district, an area of manufacturing just beyond it, then a residential area inhabited by the industrial and immigrant working class, and finally an outer enclave of single-family dwellings. Burgess was right about the urban America of 1925, he was right about the urban America of 1974. Virtually every city in the country had a downtown, where the commercial life of the metropolis was conducted, it had a factory district just beyond, it had districts of working-class residences just beyond that, and it had residential suburbs for the wealthy and the upper middle class at the far end of the continuum. As a family moved up the economic ladder, it also moved outward from crowded working-class districts to more spacious apartments and, eventually, to a suburban home. The suburbs of Burgess’s time bore little resemblance to those at the end of the twentieth century, but the theory still essentially worked. People moved ahead in life by moving farther out.

But in the past decade, in quite a few places, this model has ceased to describe reality. There are still downtown commercial districts, but there are no factory districts lying next to them. There are scarcely any factories at all. These close-in parts of the city, whose few residents Burgess described as dwelling in “submerged regions of poverty, degradation and disease,” are increasingly the preserve of the affluent who work in the commercial core. And just as crucially newcomers to America are not settling on the inside and accumulating the resources to move out, they are living in the suburbs from day one.

As used in line 68, “conducted” is closest in meaning to

View Solution